The first time I watched Blade Runner was when I was in university. I don’t remember the exact circumstances that led me to discovering the film, but I think it was featured in one of the multitudes of “10 Sci-Fi Films You Need to See Before You Kick Off This Mortal Coil” lists, and as sci-fi is pretty much my favourite genre of anything, I was eager for a new offering to devour (the film also single-handedly introduced me to the cyberpunk genre, which has been my favourite niche ever since). This is going to sound really hyperbolic, and I’m sorry about that, but Blade Runner really was one of those films that was a turning point for me. It was a revelation.

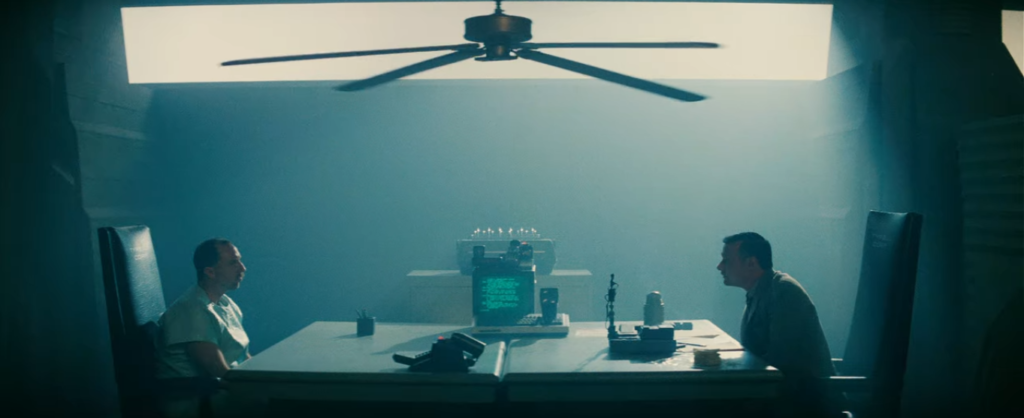

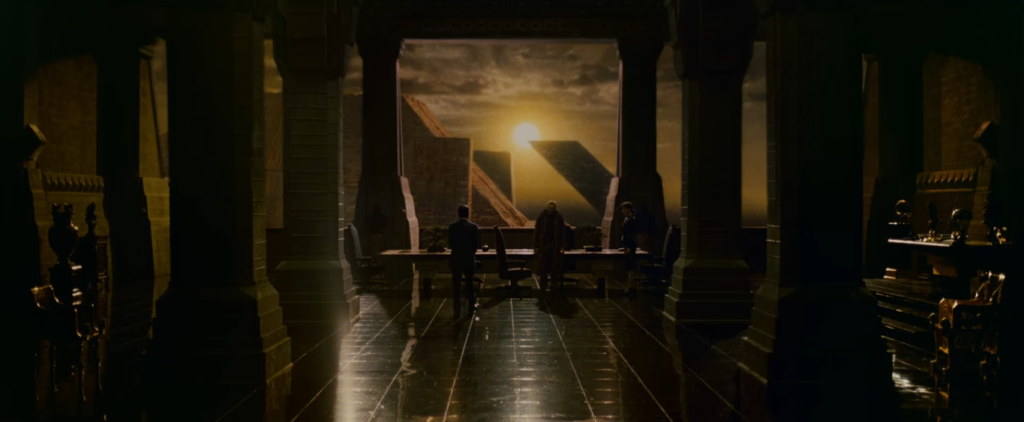

Blade Runner, released in 1982, was directed by Ridley Scott (who is also responsible for one of my other favourite films, 1979’s Alien), and is a fairly loose adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Set in the future (at least at the time of its release) of 2019, in an alternate version of Los Angeles, the film follows Harrison Ford’s Rick Deckard, a Blade Runner – someone whose job is to track down and “retire” Replicants (essentially very advanced androids virtually indistinguishable from humans). Replicants were made illegal on earth after there was a mutiny on one of the unnamed Off-world colonies, and they also have a really short shelf-life – only four years – to ensure that there is no way they can rebel. It is this short lifespan that motivates four Replicants; Leon Kowalski (Brion James), Zhora Salome (Joanna Cassidy), Pris (Daryl Hannah) and their leader, Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) to return to earth to seek a solution from their creator, Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel). Batty and his brethren may be artificial, but their desperate desire to live a longer life than what they have been given is completely human. This search puts them in the path of Deckard, who, despite being retired, is begrudgingly brought back to the police force to track the Replicants down and kill them.

The story of Blade Runner is more than just a case of “Good Guy Tracks Down Bad Guys and Defeats Them”, though, making it more interesting than other stories in the sci-fi genre. The lines between who is a “good” character and who is a “bad” character are often blurred. For example, Deckard is the protagonist and therefore by definition the “good” character, but he is in no way a spirited hero operating under a sense of moral duty – he’s essentially an alcoholic, he treats his romantic interest quite roughly (more on that later), and he’s not even particularly interested in the job he has set out to do. Roy Batty, essentially the film’s “bad” character, is in many ways more a tragic victim than an antagonist, as his plight is the same one that faces all of us, really: life is simply not long enough for all of the experiences we want to have. Batty, despite being “bad” and despite not even being technically human, has more of a human drive to live and be happy than the human characters in the film. His “Tears in the Rain” speech (written by Hauer himself) is still so poignant nearly forty years on because it captures the essence of what it means to be alive – to have all of those wonderful experiences, thoughts, feelings, memories, but then to inevitably die and have all of that disappear as if it was never even there in the first place.

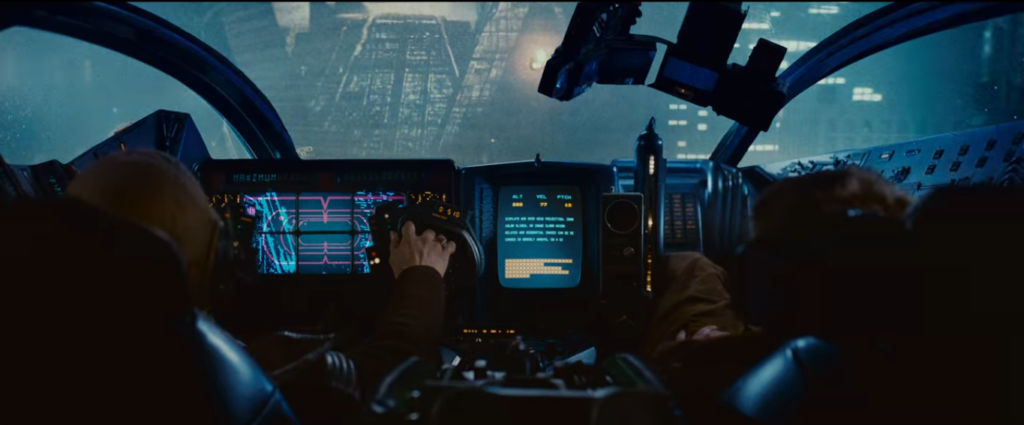

The neo-noir elements in the film extend beyond its characters. Blade Runner’s biggest strength, and also the main reason why I love it so much, is its world-building. Its version of Los Angeles is dark, smoky, gritty, but also full of technology. It is a definitively 80s view of the future; flying cars, boxy CRT monitors replete with green text, plastic clothing. Scott weaves a rich tapestry of future-world goodness with a hundred different things going on in each shot – you stare at it intensely each time and you see something new.

The brilliant cinematography and special effects in Blade Runner are evident from the get-go: the opening titles finish and straight away there is the visual spectacle of the initial establishing shot of Los Angeles, accompanied with the entrancing score from Vangelis. Immediately the scale of this world is revealed. I remember seeing this film in cinemas a few years ago and actually getting goosebumps when it started. I even used to show the opening titles and establishing shots to my English classes when we were learning about film and the importance of score.

The score is so effective because it really helps to imbue Blade Runner’s world with an atmosphere of mystique and other-worldliness, taking a place we know and turning it into something new; we know a Los Angeles, but we definitely don’t know this Los Angeles. Each new piece of music by Vangelis perfectly captures the essence of a particular scene – for example the score of the city sequences is full of industrial sounds undercut with deep synth, highlighting the foreboding encroachment of technology on this world, the scenes where Deckard is flying above the buildings is light and floaty, replicating the feeling of flying with music, the Love Theme’s saxophones give the score a bit more of that noir flavour. Overall it’s a score that juxtaposes the harshness of the city’s technology and industry with the softer beauty of its opulence, and helps to create an even further sense of wonder about this world in the audience, supporting the world-building.

However, despite how brilliant many aspects of the film are, it of course is not perfect (no film ever could be). There are three main points that drag the film down a little: the acting, the pacing, and, most importantly, the treatment of female characters.

Firstly, the acting. Some of it is good! Most of it is not. The stand-out of the film is most definitely Rutger Hauer as Roy Batty. His Batty is imposing but tragic, always on the verge of humanity but not quite there. He chases down Deckard with frantic energy and murderous intent, yet when one of his fellow Replicants dies he howls like a dog instead of crying, as if he can feel the pain of such a loss but does not know the right way to approximate it. He quotes classic literature, he describes the wondrous sights he has been privileged enough to see in his short lifespan but he also menacingly toys with his victims, knowing they have absolutely no recourse against him because of his superhuman abilities.

Unfortunately, the rest of the cast do not live up to the heights set by Hauer’s performance. Harrison Ford isn’t terrible, he just never seems to get “warmed up”, and some of his line delivery can be strangely off at times (the scene that comes to mind most readily is the one where Deckard tells Rachael she’s a Replicant – it’s just awkward). The three female Replicants, Rachael, Zhora and Pris, played by Sean Young, Joanna Cassidy and Daryl Hannah respectively, are all just fine. They don’t really have a lot to do in the film anyway. Tyrell (Joe Turkel), Gaff (Edward James Olmos) and J.F Sebastian (William Sanderson) are all relative degrees of fine as well. The worst acting comes from Brion James, who plays Leon Kowalski. James’ performance ranges from distracting at best to laughable at worst (“wake up, time to die!” will never not make me visibly wince). It’s a shame that the acting in the film isn’t always very good, because the characters and they stories they are telling are all so interesting.

Another problem with the film is its pacing. I’m not so much talking about the sequence of the scenes, as I think the overall slower pace and lack of action lends a kind of “dreamy” quality to the film that compliments its aesthetic – it makes you feel like you’re inside the world and everything is happening around you. What I mean is that that some scenes just go on too long, to the point where they can become either awkward or boring. The pauses between dialogue can be too long. The cuts between each scene can take too long to arrive. It’s a lesser complaint but a problem that I’ve noticed more and more each time I watch the film, especially this time around when I was making notes about what happened in each scene.

And finally, there’s the film’s issue with the treatment of women. There are three female characters in the film, all of them Replicants: Rachael, a very advanced Replicant created by Tyrell Corp to test the benefits of giving Replicants memories as an “emotional cushion”, Pris, a pleasure-model, and Zhora, trained as part of an Off-world kick murder squad. The first problem with the way women are treated in the film is how they are viewed. All three of the female characters are viewed in some sort of sexual light. Pris is obviously involved in sex work, and this is treated dismissively by the film (she’s mentioned last as just a “basic pleasure model” when the Replicants are being introduced to Deckard by Bryant). She’s also clearly framed in a desirable way and also viewed as such by both Roy Batty and J.F. Sebastian. Unfortunately this is largely the sum of her character, as she is given little personality of her own before being unceremoniously killed off by Deckard.

Then there’s Zhora, who too is framed to be desirable at the expense of a personality. There’s the obvious examples of her being viewed showering or dressing, but there’s also the less obvious connotation of her last name, Salome, and the historically erotic associations it has. Zhora at least can stand up for herself a bit more, and does give Deckard a bit of a run for his money when she initially escapes from him, but she too winds up dead.

And then we come to Rachael. Poor Rachael. Her plight in the film is arguably as tragic as Roy Batty’s – whilst he is a Replicant too, at least he knows he’s a Replicant. Rachael isn’t afforded this knowledge until about halfway through the film, meaning that she’s lived her entire life under false pretences and is treated by Tyrell as an object, a possession, rather than a being with thoughts and feelings. As she so eloquently puts it, “I’m not in the business. I am the business.” There’s no thought by Tyrell as to what Racheal’s response would be upon learning she wasn’t human. No real care for that at all. When it’s discovered that she knows the truth, he just takes a hit out on her.

Like the other women in the film, Rachael is also framed as extremely desirable and her purported “romance” with Deckard is actually something which she seems to have little control over. Racheal comes to Deckard’s apartment, and the film tries to present the scene as romantic with the use of close camera angles and softer music. However, it quickly takes a turn for the uncomfortable. Deckard kisses Racheal and she tries to leave but he prevents it. He blocks the door, throwing her against the wall, where she visibly recoils from his touch. She implies that she can’t rely on her emotions, as she’s still reeling from the news that she’s not human. Deckard just tells her to say “kiss me”, not bothered with her concerns. It’s honestly quite a dark moment for the character. Even the score during this part of the scene is more menacing.

I’ve read posts by people online trying to explain that scene as one of passion, as one of Rachael being afraid of but ultimately accepting Deckard’s affection, but first of all I don’t think Deckard regards Rachael with any true amount of affection (at least not immediately), and second of all, if she was afraid of this affection, Deckard forcing himself on her is not the way to assuage any fears she has. The scene makes me uncomfortable every time I watch it, and I don’t believe Racheal and Deckard’s romance at all. It’s just another aspect of Deckard’s character that proves that he is no real hero.

I really wish that the film’s treatment of women was better. Unlike Roy Batty, the female Replicants never get their moments of humanity. They never get to appear more than just the androids that they are. They never get any sense of development. The men in the film get all of this and are also never framed in a sexual way. I know that this is a problem that goes waaaaay beyond Blade Runner, but it’s something that we as a society are more and more aware of now, and older films should not be immune from that kind of criticism – we need to evaluate the things they have handled poorly so that we can move forward on more positive, equal footing.

So, we come to the final question – should you watch Blade Runner or not? Well, if you’ve been reading up until this point I think my answer is pretty clear. Blade Runner is worth watching for the world-building alone, but the story is also interesting and thought-provoking. It’s a film that rewards multiple rewatches and discussions. If you’ve read my list of my ten favourite films, you’ll know that Blade Runner is my second favourite. However, I’ve tried to remain as unbiased as possible when writing this Blade Runner film review, because although I think the film is a masterpiece, I know it is a flawed one. Just like the fictionalised version of Los Angeles that is the setting of the film, there is beauty and wonder to be found, but also weakness and instability, and maybe something a little darker underneath the surface.

BEST BITS

– All of the creative and interesting details that make up the grimy city of Los Angeles. It’s no wonder the film was nominated for an Academy Award for its art direction!

– The way the score perfectly mirrors the atmosphere of each scene.

– The costumes! I didn’t talk about them much but I love how they blend 1940s aesthetics with something more futuristic.

WORST BITS

– Some of the acting.

– The unfortunate treatment of women.

– This might be something that just bothers me but I wish there was more of a score during the final confrontation between Deckard and Batty.

FINAL RATING: 8.5/10

BUT WAIT! THERE’S MORE! WHICH VERSION OF BLADE RUNNER SHOULD YOU WATCH?

There are currently seven official versions of Blade Runner. Of those versions, only five of them are really easily accessible, and are part of both the Ultimate Collector’s Edition released in 2007 and the 30th Anniversary Collector’s Edition released in 2012. It’s important to know the differences between each of the versions because which version of the film you watch will determine what experience you get.

VERSION ONE: The Workprint Version (1982)

The original version of the film meant to be shown to a test audience. It ended up being the basis for the Director’s Cut released in 1992. It is available as part of both of the Collector’s Edition releases.

VERSION TWO: San Diego Sneak Preview Version (1982)

This version includes two additional scenes not seen before or since its showing in May 1982, and the “happy” ending sequence that was later cut from newer versions of the film. It is not available in the Collector’s Edition releases.

VERSION THREE: US Theatrical Release Version (1982)

This version was the one released to US cinemas, and contained both the infamous narrations by Harrison Ford (mercifully cut from later releases) and the “happy” ending sequence. It is available as part of both of the Collector’s Edition releases.

VERSION FOUR: International Theatrical Release Version (1982)

Originally unavailable in the US, this was the version shown in Europe, Australia and Asia, and released via home media. It included more violent scenes that were cut from the US theatrical release, but retained that version’s ending and narrations. In the US it was released in 1992 as the “Tenth Anniversary Edition”. It is available as part of both of the Collector’s Edition releases.

VERSION FIVE: US Broadcast Version (1986)

The version initially broadcast on television, with profanity, nudity or excessive violence removed. The opening crawl was also different and narrated. It is not available in the Collector’s Edition releases.

VERSION SIX: The Director’s Cut Version (1992)

This version of the film cuts the “happy” ending sequence and Ford’s narrations. It is the first version of the film to feature the “Unicorn Dream” sequence that casts more ambiguity over whether or not Deckard is human. Scott released this version after the workprint version of the film was released without authorisation. It is available as part of both of the Collector’s Edition releases.

VERSION SEVEN: The “Final Cut” Version (2007)

This version is also known as the “25th Anniversary Version.” It retains the same changes as the Director’s Cut, but expands upon the “Unicorn Dream” sequence and adds back in some scenes cut from US versions but featured in the International Release version. It also fixes some continuity errors, such as when Bryant mistakenly informs Deckard that there are five Replicants on the loose instead of four, or the dove Batty releases at the end now flying into a dark sky instead of a light one. It is available as part of both of the Collector’s Edition releases.

So which version of Blade Runner should you watch?

I recommend the “Final Cut” version of Blade Runner purely because it’s the most easily accessible and contains all of the original material that Scott wanted in the film. If you can’t access that version, however, the Director’s Cut will do just fine. If you’ve seen these more definitive versions of the film you should consider going back and watching either the US theatrical release or the International release just so you can experience the narrations and the different ending, therefore having the most complete understanding of the film.

More like this: Should You Watch Blade Runner 2049?